Even before I heard that a new Moana film is set to be released by Disney later this year, I had been thinking a lot about how this story closely mirrors that of one of my favorite saints. Joan of Arc is widely regarded as one of the best-documented historical persons of the Middle Ages. This is due largely because of the meticulous legal proceedings that concluded the drama of her extraordinary life with a public burning in the square of Rouen, France in 1431.

Her life story is remarkable for many reasons (the youngest military commander -in-chief in history, her mystical communication with saints, her virtuous conduct, her astonishingly successful military campaign to free France from English rule, etc.). Her legacy to the French people and inspiration to the rest of the world can hardly be overstated (Mark Twain was a huge fan). But in this post, I’d like to reflect on the narrative structure of her story as a whole, which reveals the pattern of how the feminine restores the world “from below", and how this is echoed imperfectly but insightfully by the 2016 Disney movie “Moana”.

The story arc of Joan

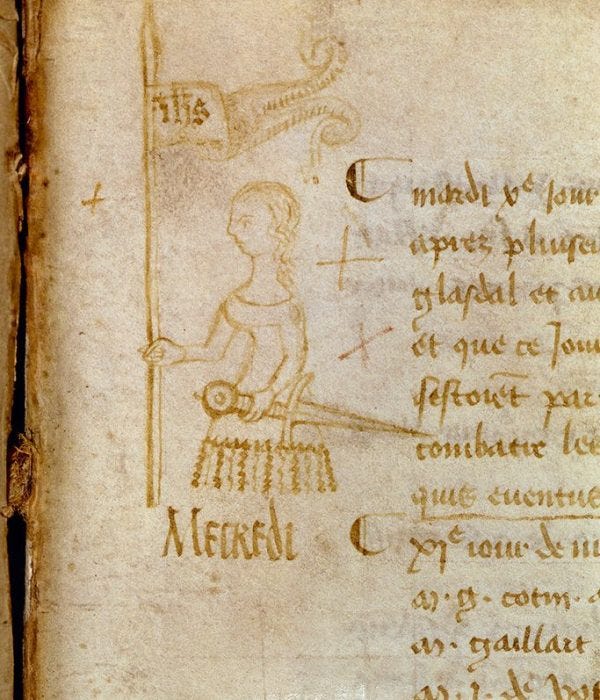

The basic story of Joan of Arc is that a young peasant girl hears heavenly voices which give her a mission to save France from the invading English army. To accomplish this, she is told to go to Chinon and bring the rightful royal heir (“the Dauphin”) to the ancient place of crowning kings (Rheims Cathedral). Along the way, she has a banner made for her to wield in battle so that she may inspire her soldiers. Although she is also said to have been given the sword of Charlemagne, a powerful relic of the most famous Frankish King, she never uses it in battle except to hold aloft and urge her men forward.

After several miraculously successful battles which push back the English, Joan finally clears the road to Rheims and stands by the Dauphin as he is crowned king of France. “The Maid of Orleans” wins the hearts of the people and puts new hope into the hearts of her men, but the new King is weak and ungrateful to his savior. When the English capture Joan in battle, he does not lift a finger to save her. The English clergy conduct a show-trial to condemn her to death by burning at the stake (like a witch or heretic), but cannot find any grounds for doing so other than cross-dressing. This decision was later rescinded by a higher court, exonerating Joan -who remains a national heroine- and she was eventually proclaimed a saint of the Catholic Church.

How a daughter saves her father

If you boil it down to its most primordial elements, the story of Joan is about how a daughter saves her father.

It is a curious pattern, and one that postmodern story tellers have been very interested in for the past several years in pop-culture. (see: Captain Marvel, WonderWoman, The Woman King, etc.) Unfortunately, the postmodern stories fail to adequately accomplish their goal because they are not going far enough in the right direction. Their mistake comes from assuming that feminine heroines must imitate the pattern of the masculine warrior. Unfortunately, they thus discard the hidden potential of the feminine.

I say it is a movement “from below” in the sense of “from the vantage point of the Earth or from under a higher authority”, rather than “from above” which is from the vantage point of a higher authority or from Heaven. (see my other post about Charlotte’s Web for how the feminine saves “from above”)

We learn from Joan that the daughter saves her people and father “from below”, by rallying attention and inspiring them forward. This is the pattern of ‘the muse’, the feminine which calls forth the masculine. She does not replace the masculine, or mimic his moves, but rather, she cries out to him and urges him to go forward with courage.

Joan is in the role of the daughter, not the mother, nor the bride. After all, she is known as “la pucelle” (the maid). Paradoxically to post-modern sensibilities, she does not save her people by violence - since she never once killed a man with her sword. Instead, she saves her people by rallying them together under her banner. She brings them together by focusing their attention on herself, while she herself is under her banner, focusing on the sacred icons embroidered on it.

Moana is almost Joan

Among the many recent attempts in pop-culture to explore the theme of how a daughter saves her father, I believe none comes as close to Joan as the 2016 Disney movie “Moana”.

In this animated cartoon, the protagonist is a Polynesian princess “Moana”, who is given a mission by the spirit of the ocean to save her people from an encroaching blackness by restoring the “heart of Tafiti". This is a magical artifact that was stolen by the man-child demi-god Maui from the heart of the world "the mother island of Tafiti”. She is instructed to find Maui and bring him back to the heart of the world to restore the artifact and stop the impending doom. Along the way, she and Maui battle a giant crab, coconut pirates, and eventually come to the final test. Maui fails to restore the heart, and instead leaves Moana alone to pass through the fire-goddess Te Kā. Moana uses her power of recognizing hidden identities to see Tafii within the fire-goddess and thus restores the heart by herself, ending the plague and saving her people.

By now I think you may be able to see how Moana nearly follows the pattern of Joan.

Both Joan and Moana are given a mission by supernatural beings to save their people.

Both Joan and Moana are instructed to bring the masculine hero to the ‘heart of their world’ to restore order and stop the invading doom.

Both Joan and Moana are abandoned and betrayed by their masculine counterpart after many successes together.

Both Joan and Moana stay true to their mission despite being betrayed.

Both Joan and Moana pass through fire at the end of their quests.

Even their names are similar! (In some Romance languages, Joan is “Joana”)

Who carries the identity?

Indeed, the correspondences between these two stories are astounding. They even share an affinity for their banners (Moana’s banner is her sail). I think the reason for this is that they are both based on the question of how a daughter can save her people not by violence, but by more subtle, feminine ways. Nevertheless, they diverge at the most crucial moment in the story, and it has to do with the question of identity, or “who carries the heart?”.

In the case of Joan, the ‘heart of France’ is carried not by “the maid”, but by the Dauphin. This concept is a fundamental pattern that needs to be explained more here. The heir to the throne “the Dauphin” is the prince who carries the lawful lineage that is entitled to the crown. He is symbolically the ‘first born son’. The one who carries the seed, the promise (the identify of the kingdom) forward into the next generation. Especially when besieged by the English and the Burgundians, the fate of the kingdom, the dynasty, and (by extension, the people) of France rests in his person. It is the identity of France as one whole, united entity that is at stake here.

This is contrasted with the story of Moana, which proposes an alternative, modern anthropology at odds with the ancient symbolic world of Joan. Although Maui at one time possessed (the ‘seed’ of the world) the “heart of Tafiti”, he lost it in the ocean. The seed-bearer lost the seed. This is akin to when a royal lineage is broken or diluted with other bloodlines. Maui is justifiably left on a deserted island for a thousand years, aimless and without purpose as a consequence of stealing and losing the seed of life. Like the terra-forming Titans imprisoned in Tartarus, Maui is trapped on a bare rock in the ocean. So far so good.

But when the spirit of the ocean finds the heart of Tafiti, she does not return the heart to Maui, nor begs him to undo the damage he had committed. Perhaps the ocean was ‘burned’ by Maui and sought a more sympathetic helper. Instead, the ocean chooses a young girl (Moana) to carry the heart.

It is here at this point where the two stories diverge symbolically.

Moana as a single mother

Thus the “calling of Moana” is more akin symbolically to an upside-down version of the ‘Annunciation’ of the Virgin Mary than the “Voices of Joan” because the young Moana receives the divine seed of life from “below” (the chaotic ocean) rather than from “the heavens above”. 1 In this way, Moana is in the role of the pregnant mother who bears the true lineage of the kingdom. (This is contrasted with Joan who never ‘bears the seed’ of France, but rather urges the ‘seed-bearer’ forward).

When she brings the heart of Tafiti back to Maui and asks him to restore it to its proper place, something very interesting happens. Maui acts like a deadbeat dad who is introduced to the child he didn’t know he had. He is afraid of taking on the responsibility of his “seed” and attempts to abandon it and his ‘baby-mama’. He is concerned about worldy honor, fleshly power, being recognized for his accomplishments, and does not want the problems that entail carrying the ‘seed of life’. Nevertheless, he is convinced by the forceful power of the ocean to carry on against his wishes.

For the portion of the story when they travel on the canoe together, it has the potential to become an image of integration. The masculine and the feminine life-bearers traveling to the center of the world is a powerful image of meaningful human community and is a microcosm of the scenes of the voyaging ancestors earlier in the film, as well as the ending scene of the new voyaging villagers. However, this integration is flawed due to Maui’s immaturity and proves not to last.

When Maui becomes frustrated and abandons Moana, as he inevitably must do because of his lack of commitment, she decides to journey on without him after encouragement from the spirit of her grandmother. At this point, she does what many single mothers find themselves doing as well: buckling down and getting on with it alone. Like Joan of Arc in the hands of the English, Moana is alone and abandoned by her supposed protector. But unlike Joan, Moana’s quest is not yet completed.

Coming to the center of the world, she sees that the Mother Island is hidden within the fire-goddess Te Kā and returns the heart of Tafiti to her. Significantly, although Maui comes back, he proves counterproductive in the final confrontation with Te Kā since he attempts to battle the fire-goddess instead of seeing “who she really is inside”. Thus, Moana implants the seed of life in the mother island herself and does the job that Maui was supposed to have done.

There are many problems with the resolution that Moana proposes

I think you can see now that there are many problems with the resolution that Moana proposes.

Instead of finding true integration with her counterpart (because of his inability to accept the responsibility), Moana takes matters into her own hands. By her action of putting the seed of life into the mother island (which even in the film was never her job to do, since it is supposed to be Maui’s responsibility to restore what he stole), she even tacitly disobey’s her grandmother’s original mission.

After all, what is the role of Maui in the story if Moana could do the job by herself? He never actually protects Moana from the giant crab or the coconut pirates (she gets them out of those scrapes by herself). According to the film, the only thing Maui ever did for Moana was to teach her to navigate the canoe on the ocean. That is fair enough, but her own father could have (or was supposed to have) taught her those skills himself. Seen in that light, Maui is actually a stand-in for the wisdom of her father and her ancestors.

How a daughter saves her father

These two characters (Maui and Chief Tui) act as counterbalances in the story, and beg for integration, which eventually comes about partially in the end. Both are physically large men who once sailed on the open seas, but then had to live on a single island after a major catastrophe. But whereas Maui remains a solitary self-absorbed man-child, desiring to sail beyond his island prison, Chief Tui embraces a communal sedentary life and accepts the responsibilities which that entails. However, the excess of Chief Tui is found in his inability to allow villagers to sail beyond his own island. By the end of the story, Chief Tui presumably gains new courage after his daughter demonstrates her new voyaging skills and she sets sail again with half of the village. In this way, he integrates his opposite character (Maui) in a more balanced way since he sails together with his people, while Maui continues unchanged and solitary.

It is for this reason why I said in the beginning that Moana attempts to be a story about how a daughter saves her father. She brings about this change in two ways, by restoring the seed of life into the mother island (thus protecting the islands from death), AND by learning voyaging skills (thus inspiring courage and confidence in her father and village). However, there is nothing uniquely feminine about either of these two actions. Indeed, both of these could have easily been done by a teenage boy. The story would actually be much more symbolically coherent that way. Sadly, seen in this light, this is yet another example of a feminine character attempting to do the job that was meant for a masculine character.

Contrast the proposal of Moana with Joan’s story, which is based on her ability to save her father, NOT by doing the job of her masculine counterpart, NOR by learning prized masculine skills, but rather by inspiring her soldiers, and indeed by capturing the hearts and imaginations of her entire country to believe in France once more.

If Joan was in Moana’s shoes, what would she do? The movie would probably be the same up to the point of meeting Maui. Then, Moana would find a way to sincerely convince Maui of their shared divine quest. (Moana was unable to adequately do this.) They would go on to fight a host of bad guys on the way to the Mother Island and learn some navigating skills as in the movie. But when they come to Te Kā, Moana would recognize immediately that she is Tafiti and tell Maui where to put the heart. He would then restore the heart and thus repay his debt. He could then skirt off to sail the world again, or (for more complete integration), he could settle down on TaFiti and guard the heart from encroaching baddies. The film could end there, or (to be truer to Joan’s pattern), there could be a final battle. All the oceanic enemies would descend upon Tafiti and capture Moana, demanding a trade for the heart. Maui would refuse the deal (either from callousness or fidelity to his new oath to protect the heart), and the baddies would throw Moana into a volcano as a martyr. She would bravely sacrifice herself, like Joan, to save the world. This would compel Maui and Chief Tui’s villagers to hunt down and destroy the bad guys in vengeance, as in the case of France. At last, peace would come to ancient Polynesia.

This structure would follow more closely to that of Joan of Arc, but why is it important?

Recognizing identity

Amazingly (despite the imperfections in the Moana story), the key superpower of Moana and Joan is the same in both stories: recognizing identity. When Joan first meets the Dauphin, she convinces him to trust her by recognizing him (even though she had never seen him before and he is disguised) in a crowd. This is the same power that Moana displays in the climatic scene where she recognizes Tafiti ‘under the disguise’ of Te Kā. Both Moana and Joan have the power of recognizing identities under disguises. This is reflected in Moana’s many song’s about “knowing who you are”.

In Moana’s story, she missed her opportunity to save Maui when she first met him on his rocky prison. It was there that she should have seen through his appearances to understand “who he really is inside” and thus win him over to her cause. Instead, she was perplexed and her stuttering prompted Maui to launch into his “Your Welcome” song, which marks the crucial break with Joan’s pattern. (She sees later that Maui is seeking approval for his great feats, but this comes too late to make any narrative difference.)

Incomplete integration creates a downward spiral

Although Moana’s story nearly follows that of Joan, decisions taken in the narrative structure cause the pattern to break in several key points. The result is that the main conflict in the story is not really resolved. Since he in no way paid for his error, Maui still owes a debt to Tafiti for stealing the heart. In other words, the integration between the two gods (the feminine and the masculine) is left incomplete. Instead, the power of the feminine goddess is restored, but by improper means. This keeps the masculine god in a reduced child-ish state, and unable to consummate complete integration with the feminine. Of course, the post-modern zeitgeist would not tolerate a scene of such powerful integration (Maui restoring the heart would be too ‘traditional’ and ‘normative’).

Without a doubt, the resulting icon of Moana paints a world that fits the prevailing post-modern worldview: the large abundant earth-goddess doling out toys to the immature and sterilized man-child demi-god. The problem with this picture is that it is woefully short-sighted and incapable of lasting very long. Without integration, the heart will be stolen again by another monster or demi-god (perhaps Maui will try once more), and the cycle will continue. It is a good story to describe how the post-modern story will play itself out, but NOT a good story for how to get out of this downward spiral. For that, you will need a Joan, not a Moana.

The way that this narrative structure could have been remedied is if Moana somehow received the heart of Tafiti “from above”, ie. : if Moana was a mermaid that caught it underwater as it drifted down to her from Maui’s crashing into the waves above.

Interesting! I didn't see the movie, but the combination of 'man child' and 'losing the seed' seems an obvious, if accidental, nod to the need for seed to be borne and placed-with-intention/protection/reverance by actual grown men and not pissed away by boys playing with themselves!

Very interesting! A minor note: Joan of Arc died at Rouen (in Normandy, which had a strong English presence) not at Reims.